Table of Contents

Open Table of Contents

Introduction

League of Legends isn’t a fighting game. However, it is a game in which fighting happens a lot, which means it’s not far off. The study of League’s gameplay could learn a lot from fighting games, whose terminology and concepts have been refined for decades.

One such concept is a “string.” Combos, in the traditional sense of an unavoidable sequence of hits, aren’t as ubiquitous in League as in fighting games. Instead, League tends to have more “strings”: a sequence of actions that aren’t guaranteed (because of the nature of League’s movement), but function well together.

Why would you want to press multiple buttons?

The question of “why strings” is worthy of examination. It’s important to note that you don’t need to take actions in a sequence. You can take actions at any arbitrary time, with or without the context of other actions. Actions in isolation, however, generally have lower value than they do in combination with others. Players understand this idea intuitively, if not explicitly. If a target is at 300 HP, 400 damage now is better than 200 now and 200 later. The formal reason involves time and variance. The informal reason is that “shit happens.”

The time between actions means “something” can happen that affects the outcome in a way you can’t account for. Maybe the target moves away. Maybe someone will heal them. Maybe your teammate steals the kill. The faster a sequence happens, the less variance enters the equation.

I’d love to wax poetic about variance, but that topic is more fundamental than pressing several buttons together and will require its own essay. For now, take the following definition for granted, and I’ll prove it eventually™. Variance for what we care about in games is the idea that an outcome can deviate from an expectation. Variance isn’t just “rng,” either. We can categorize anything out of our immediate control—enemy clicks, ally decisions, your own mistakes—as the manifestation of variance. Generally, variance is bad: we want things to happen according to expectation because it lets us make decisions on the future, even with imperfect information. As such, much of how to get better at playing games has its roots in controlling and lowering variance.

Strings are a label on the general act of making decisions in a sequence. Just because you construct a string, however, does not mean your construction is the best permutation of its constituent components. An optimal ordering for each situation generally exists. A lot of this is rooted in lowering variance. You want your low investment options earlier to decide whether or not to continue. You want your high-variance options after your variance-reducer options because you don’t want your success to come down to chance. The order in which you arrange the actions in a string and the number and type of actions within a string determine its optimality for a given scenario.

What does “optimal” mean? The discussion surrounding optimization also deserves its own essay, but we’ll primarily focus on the balance of variance vs. value for the purposes of discussing strings. The decisions we commonly classify as “optimal” lean towards low variance and high value. In more combat-specific terms, we want big guaranteed damage.

Substring components

Strings are composed of several smaller classes of actions.

- Starter

- Filler

- Finisher

- Extender

Not all strings have all parts, but most strings have at least a starter and a finisher.

Starter

Starters are the first actions taken in a string. Generally, they serve to set up the rest of the sequence. These are the actions that first put you in tension with a target. The aim of a starter is several-fold: they can reduce the overall variance in outcomes, increase the value of proceeding actions, and/or gather information.

Starters come in many forms. Crowd-control (CC) is often used as a starter: reducing or removing the target’s ability to react is as good as it gets when you want to guarantee value. Landing a skillshot on a fully actionable target is a situation with highly varied outcomes. You can miss, and your opponent can dodge! However, if the target is stunned or rooted, then a hit—and the corresponding damage—is practically guaranteed. Some examples of CC starters include Xerath E, Sejuani R, and Nautilus Q. Slows are also very applicable.

Crowd control is not the only valid option for a starter. Positioning is a large variable in combat, so actions that put you in a good position are also possible starters. This encompasses dashes and blinks, but simply walking at the target and being within effective range is a universal option for all champions. Positioning is (or it should be) an active choice. Consciously or not, you choose to put your champion in or out of various threat ranges. Moving your champion into your opponent’s range is an option to start an interaction, and should be considered when you want to expend as few cooldowns as possible.

Another valuable use of starters is for the collection of information. Because starters are usually low in damage, they’re comparatively low in investment compared to other options. Even with your main starter gone, you probably still have much of the damage in your kit left, so you can at least participate in any interaction that breaks out afterwards, successful starter or not. The low damage cost of starters lets you throw them out as a conditional check for the success rate of the rest of your string. In programming terms, starters serve as an “if” statement. If your starter succeeds, you can invest the rest of your string knowing it’s also likely to succeed. If your starter doesn’t succeed, you can drop the string and save your resources and damage for later.

Filler

Filler actions are the small, “nonessential” actions between the starter and finisher. These are your auto attacks and core damaging abilities: Amumu E, Ziggs Q, Brand W, etc. They’re generally pure damage actions with limited utility and have low costs or cooldowns. Because filler actions are low-cost, you can afford to take multiple within a single string. The real limiter on the amount of filler a string contains is time: you only have so much filler you can include before the situation changes, usually in the form of your target leaving your range. A significant portion of a string’s value is from its filler.

A distinguishing quality of filler actions is their significant opportunity cost: you’re using time and resources to take filler actions, which could be used for extenders or finishers. With each filler action taken, you add some variance to the string, which may or may not affect the outcome of the entire string. This is the essence of being greedy—you’re making the conscious choice to add more value with the tradeoff of more risk. Greedier strings have more filler because they’re speculating on a higher payoff.

A note on basic attacks

Basic attacks (also called auto attacks, or autos) are a part of every champion’s kit and are an omnipresent option you can take. They’re a low-commitment value addition because they’re generally fast and cost nothing but time. In particular, some actions follow up very well with auto attacks by canceling the rest of the basic attack animation and/or forcibly resetting your attack timer instantly (known as attack resets or auto resets). Attack resets and other animation cancels for basic attacks can discount their time cost heavily, letting you weave a few in your string. In the context of some champions, basic attacks cease to exist as their own independent action, and instead are treated like an optional add-on to more committal actions. Think of it this way: if you’re already going to fit a quick animation spell in your string, you might as well stick a low-cost auto in front. The relative value of this discounted “free” auto decreases as your spells do more damage and combat speed increases, but it’s always an option available to you, especially if your champion has an attack reset in your kit.

Finisher

Finishers are the final actions taken in a string. These are generally high-cost actions with high variance and value, meaning they benefit greatly from setup. In fact, on many champion kits, these abilities explicitly reward using them at the end of an engagement, and are sometimes straight-up non-functional if used earlier. Some actions categorized as finishers are abilities like Syndra R, Sett W, and Xayah E.

This class of action also tends to force an end to an interaction. After a finisher, your champion runs out of useful actions in combat, you gain some defensive benefit that helps you disengage, or you generate enough threat that your opponent dies or is under mortal threat from trivial follow-up. Strings exist to set up finishers, since they frequently have little guaranteed value in isolation.

Extender

Extenders are a special type of substring action. The purpose of an extender is to force an enemy to continue interaction when the sequence would end otherwise. Extenders are optional and appear mostly in greedy strings when you want to add setup mid-interaction. Most starters can be used as extenders, where instead of setting up the string with some strong utility, you can hold it for later for extension and choose a different starter.

Greed vs. Fear

There is no universal solution for constructing the perfect string. When you perform a string, you’re speculating on how much risk you’re willing to take and what cost you’re willing to invest, all for an expected return. In line with this financial metaphor, you can think of your options ranging from “greedy” to “fearful.”

CNN’s Fear and Greed index, from which I borrowed the concept.

Greed is the prioritization of higher value over lower variance. When greedy, you’re throwing caution to the wind and letting the variance in. Greedy strings take longer, commit later, and include more filler. Reminder: more filler in your string means you do more damage! It also costs more time and risk.

Sometimes, the costs are well worth it—if you hit your target with enough Sett autos before your Haymaker, you could kill them with the extra value. Other times, however, the increased variance will cause your string to leave your range or fight back, resulting in a lost payoff or direct punishment.

Fear is the prioritization of lower variance over higher value. When fearful, you want as little variance as possible in outcome. Fearful strings are short and bitter. You take less risk and look for guaranteed results, but it comes at the cost of possible value. The fearful string could 100% guarantee your Sett W on a target, but they might live by a sliver—a sliver that would only have taken an extra auto, had you been willing to greed a little more.

When do you choose what kind of string?

The central decision of weighing greed and fear in your string construction depends on how much you can account for variance in other ways. The main variance, of course, comes from your target. People don’t like to risk their lives [citation needed], so it’s up to you to guess how they will react, and what will happen when they do. Your answer to the situation determines how greedy/fearful you can/should be, respectively. If you have a high degree of confidence that you can predict the outcome, you should be greedier. If you have low confidence about the outcome, you should be more fearful.

Okay, but what if I don’t know anything?

Then it’s time to learn. If you’re in-game, make a hypothesis about the situation, pick a string you plan on performing, and implement it. Experiential learning is scary but teaches lessons quickly. You’ll know exactly what goes right and wrong as soon as you click the buttons. Additionally, the pressure of a real game adds to your mental stack, so any learning from the situation is immediately practical.

If you’re out-of-game, watch someone better than you in the same situation. Note a decision point where they begin a string, compare their solution to yours, and then try to remember it for yourself. Studying is a very useful way to find a decent baseline by aligning yourself with the “experts” for answers. Do note, however, that putting your studies into practice will always be harder than you expect. Your mental stack heavily influences your ability to make correct decisions under pressure, so don’t expect to execute exactly as you drew it up.

Sett Examples

Sett gives us a pretty nice kit to illustrate the idea of strings. We can first label the actions in Sett’s kit as parts of a string. For the sake of simplicity, let’s focus on his basic abilities.

- Autos: filler

- Notably, Sett’s passive makes every other basic attack faster and stronger, so when maximizing for damage, Sett prefers to commit to two autos at a time.

- Q: filler (auto cancel)

- W: finisher

- E: starter/extender

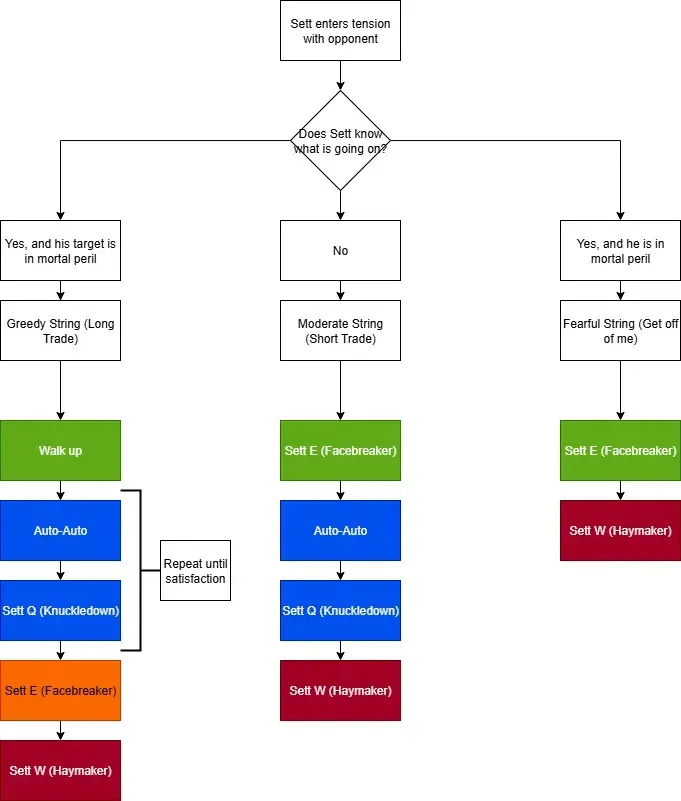

Here are three example strings that Sett generally uses to trade in lane before he hits level 6.

As noted above, the greedier Sett’s string, the more Qs he fits in, and later he uses E and W. In theory, the greediest possible string would just be auto-attacking someone to death, but it’s extraordinarily unlikely you’ll meet such a perfect punching bag. Let’s go through the reasoning behind why you might use each string and place ourselves in the Boss’s shoes.

Neutral String

In this string, Sett uses his E, Facebreaker, as a starter, since it’s a hard CC that lowers the variance of his follow-up. Because this string begins with a high-commitment option (E, which has a 16-second cooldown at rank 1), he also gets decisive information upon using it. If he misses his E, he probably isn’t willing to continue the rest of the interaction. Sett has trouble staying on his opponent as a melee champion with inflexible mobility, so generally, he can’t guarantee much beyond the initial filler.

During the E stun, Sett presses his Q, Knuckledown. Knuckledown is Sett’s main damage button, and thus the best filler option for value. Because Sett Q is an attack reset, he can also fit in a cheeky auto-auto beforehand for relatively low time invested. He gets off four basic attacks that are effectively guaranteed because of the successful starter.

Sett finishes with W, Haymaker, to cap off the string. The Haymaker sweetspot isn’t guaranteed, given that the stun from Facebreaker has worn off, but W’s high overall damage and large shield granted to Sett is a strong deterrent to any further interaction. The target likely backs off, and the string ends.

Neutral strings are generally used in lane as a short trade, where Sett wants to exert some offensive pressure but isn’t willing to all-in (put his life on the line and invest everything). He wants to get in, punch his foe, and push them out. The string is conditional on landing the initial E, so Sett can decide early on when he wants to continue. Neutral strings are a good baseline: seeing how your opponent responds might inform you on how to adjust for the next engagement.

Greedy String

In this string, Sett initiates by walking toward the opponent. He might consider using the movespeed from Knuckledown as an approach tool, but he also might do nothing but click towards his target. Movement is very low commitment, and Sett wants to hold his high-commitment actions until later to cram in as much filler as possible. He takes as many auto-Qs as time and his opponent will allow to maximize every bit of “free” damage.

In the middle of the string, it is not unlikely that the target will attempt to escape or dissuade Sett from continuing, given that Sett is very advantaged in close-quarters combat. Here, Sett uses Facebreaker, not as a conditional starter for the sequence, but as a way to forcibly continue it. If the target leaves Sett’s auto attack range, they exit the interaction entirely, so Sett’s goal is to keep them within his range as long as possible. He pulls the target back.

At the end, Sett finishes the interaction with Haymaker, but this time, he prioritizes landing the sweetspot true damage. With the stun or displacement from his E, he can effectively guarantee a perfect W sweetspot to the face, heavily damaging or even killing his target.

Greedy strings are for when you can “get away with it”—when you can account for more variance and risk through your knowledge and find the higher payoff. The examples of a greedy string are long trades and all-ins. If you know where the meddling jungler is and have a strong estimate for your total damage, taking the greedy string will secure you the kill.

Fearful String

In this string, Sett only wants to get his Haymaker off quickly. His starter is Facebreaker for a reliable CC tool to set up his next actions. With his goal being to cash in on his biggest value button as fast as possible, the only follow-up to the E stun is W. During the stun duration of E, he sends his W and tries to guarantee his best ability before anything else happens.

Fearful strings are when the likelihood of failure is high and the punishment for failure is game-losing. Maybe Sett is getting tower dove, and he’s under threat of losing several waves. Maybe Sett is in the middle of a teamfight, and his death is inevitable. In these situations, the outcome of your output has extreme variance, and you have limited information or time to create a better solution. Above all, few actions are of higher value than no actions. This is the purpose of the fearful string. Guarantee whatever value you can, and think about the rest later.

Conclusion

Strings are a useful framework to describe how combat works in League of Legends. Gameplay isn’t a vague vibe check but the implementation of actual inputs with actual consequences. Consciously or not, players are constantly weighing greed and fear in their decision-making process, informing the sequence of actions they take. Taking a step back and abstracting the process of constructing a string helps with understanding the game at a more granular level. It’s also (hopefully) helpful in improving at League directly—breaking down how good players construct strings informs how you should approach the greed-fear spectrum for your situation.

There’s much more to say about strings and optimizing combat in general, but scope has already crept up on this essay. If you thought what I think about has been interesting, feel free to check out more of my stuff on this website.